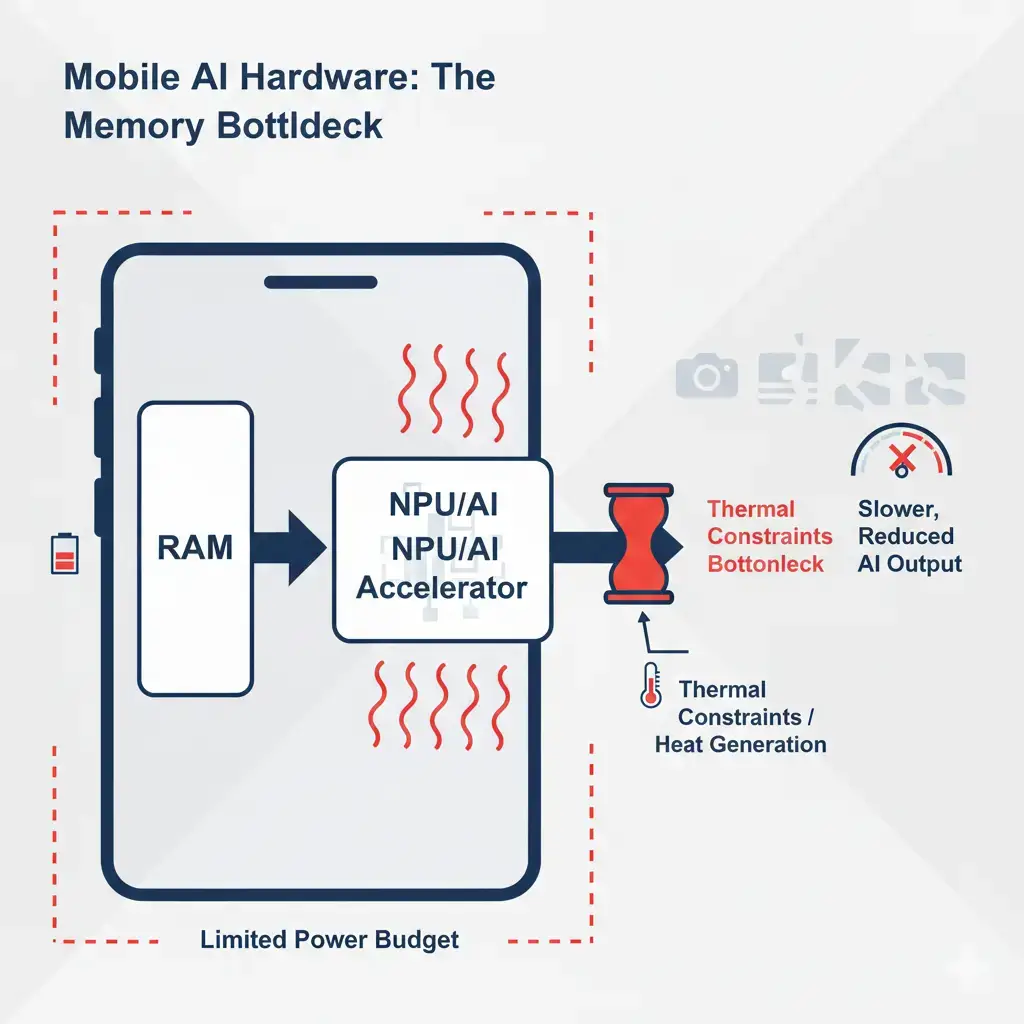

On-device AI performance is frequently constrained by memory bandwidth and capacity rather than raw compute power. These on-device AI memory limits restrict model size, increase thermal pressure, and often force trade-offs between local execution and cloud fallback.

Table of Contents

This article examines on-device AI memory limits across bandwidth, capacity, and thermal behavior in modern mobile SoCs. A new smartphone might promise on-device generative AI, but in practice, attempting to summarize a long document or generate complex images locally often leads to significant slowdowns or noticeable device heating. This behavior frequently highlights the gap between advertised peak performance and what can be sustained under real-world loads, a fundamental challenge rooted in the architectural constraints of mobile hardware.

Similarly, a drone’s real-time object recognition system, despite its NPU boasting high theoretical peak performance, may exhibit intermittent degradation during sustained, complex scene analysis. Such issues often arise because the NPU exceeds its thermal design power for extended periods, underscoring the critical engineering tradeoffs inherent in edge AI deployments.

These aren’t always compute failures; instead, they frequently stem from on-device AI memory limits and memory bottlenecks.

Effectively, on-device AI performance is often constrained by memory limits, which dictate the complexity of models that can realistically run locally and how efficiently they perform, shaping the practical balance between on-device AI vs cloud AI execution. This directly ties into the critical balance between model size and device feasibility. While the raw compute power in Neural Processing Units (NPUs) has surged dramatically, the engineering challenge of feeding these powerful engines with data fast enough and in sufficient volume remains paramount for mobile and edge devices.

Why This Matters

This section explores the practical impact of on-device AI memory limits on user experience, device stability, and the feasibility of local AI workloads. These consequences directly impact user experience, device functionality, and the overall viability of local AI applications.

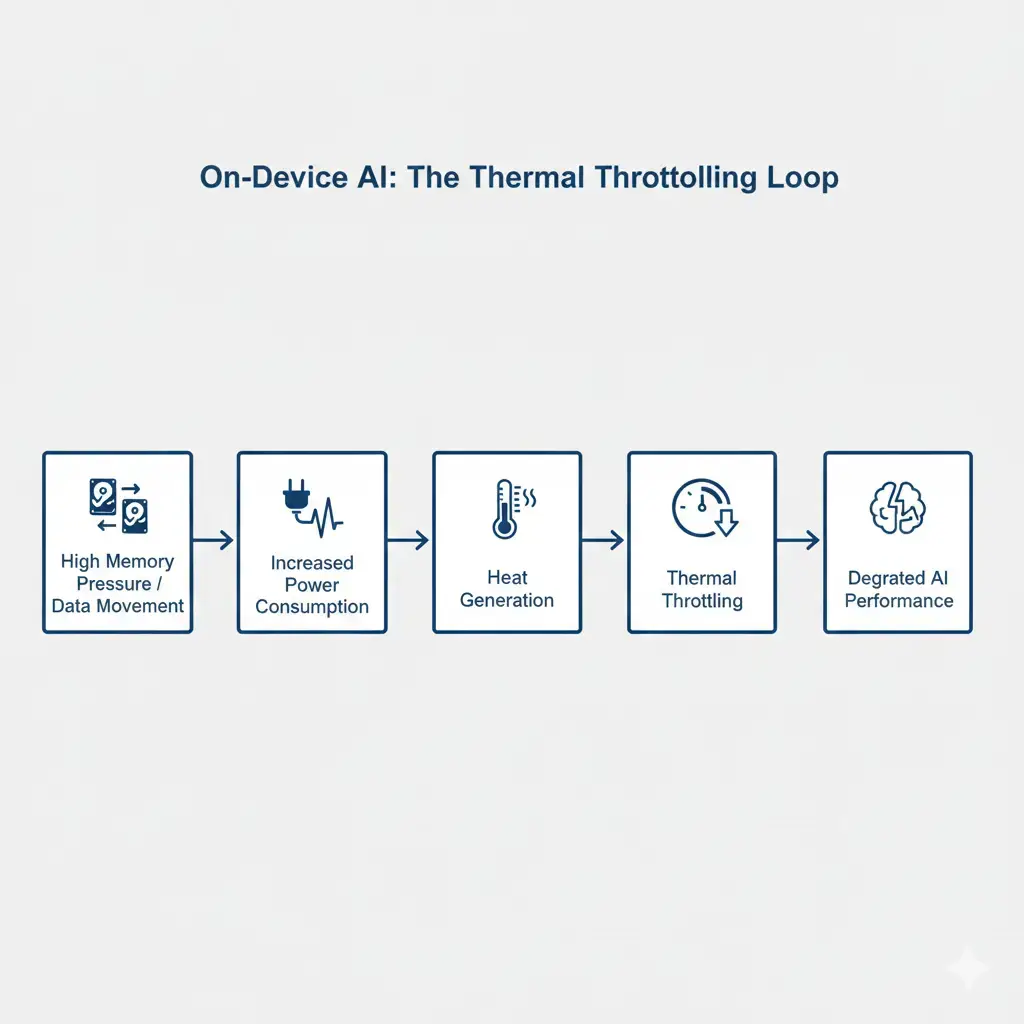

- Thermal Throttling: Constant data movement between different memory tiers consumes substantial power, generating heat. Mobile devices typically limit sustained operation to a few watts, making heat dissipation a critical factor. When these limits are exceeded, the device is often forced to reduce clock speeds, significantly slowing down AI tasks.

- Memory Pressure: Large models, even after optimization through quantization, can still exceed the available LPDDR capacity. This can lead to application crashes, extremely slow inference, or the complete inability to load the model. Smartphone RAM ceilings, commonly 8GB or 12GB, represent a hard limit for model size.

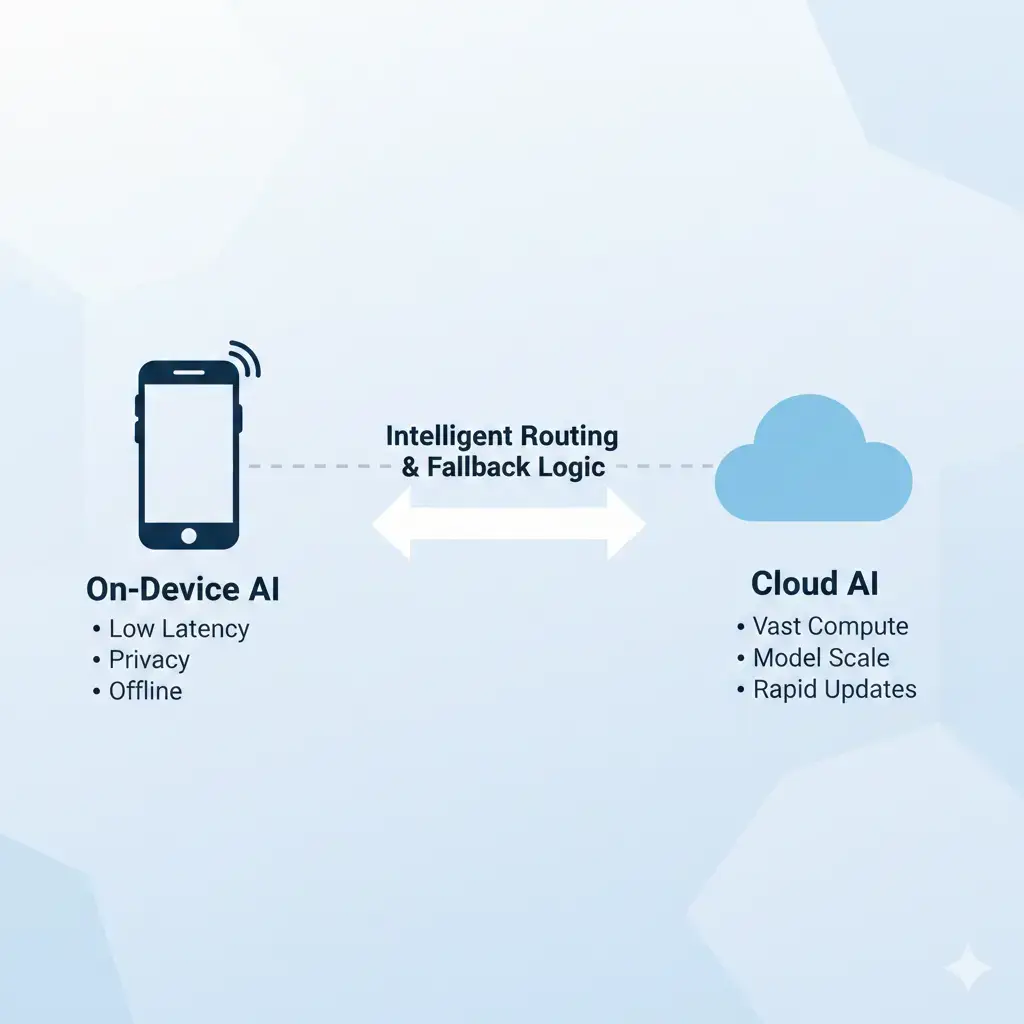

- Cloud Fallback: When local resources prove insufficient, devices frequently offload complex AI tasks to the cloud. This introduces unwanted latency, raises privacy concerns, and creates a dependency on internet connectivity, highlighting the ongoing tension and necessary balance between edge and cloud processing in real-world AI applications.

- Inconsistent AI Behavior: Aggressive quantization, while necessary to fit models into memory, can degrade accuracy and result in unpredictable or less reliable model outputs. Furthermore, memory constraints often lead to limited context windows for LLMs, causing models to not effectively reference earlier interactions. A context window defines the maximum amount of input text an LLM can process or ‘remember’ at one time.

How the System Works

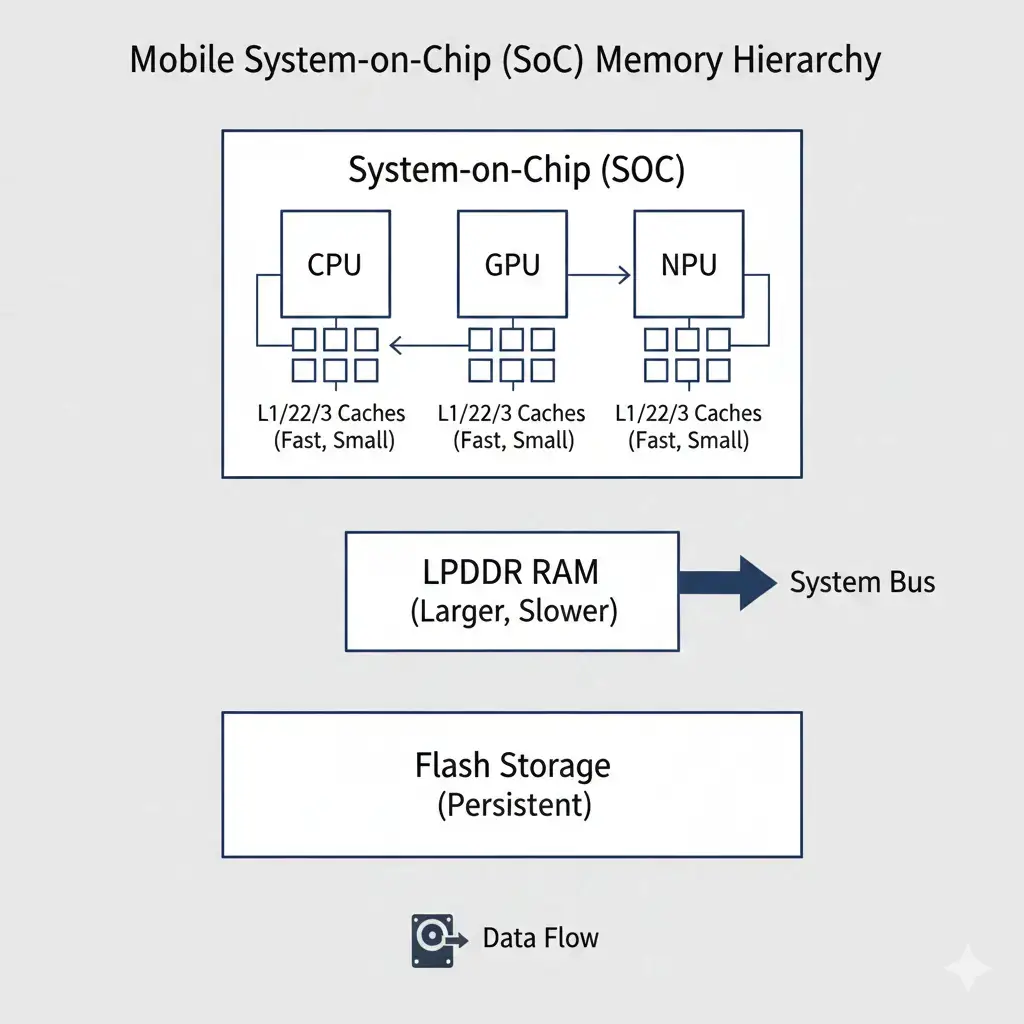

This section outlines the fundamental architecture and operational principles of an on-device AI system. Grasping these basics is key to understanding how AI models are executed and where performance constraints originate.

At the heart of on-device AI memory limits lies a complex interplay between various processing units and a tiered memory hierarchy, coordinated through system-level frameworks such as Android’s Neural Networks API. Each component plays a specific role in executing AI workloads. The System-on-Chip (SoC) typically integrates a Central Processing Unit (CPU) for general-purpose tasks, a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) for parallel processing and graphics, and a Neural Processing Unit (NPU) specifically optimized for AI operations. These units collectively perform the billions or trillions of operations required by modern AI models.

Crucially, memory components store the vast amounts of data that AI models operate on. This encompasses the model’s learned parameters (weights), the input data (such as an image or audio clip), intermediate activations generated during processing, and the final output results. Intermediate activations are the outputs of layers within a neural network before the final output.

Hardware Architecture Overview

This section provides an overview of the hardware architecture, focusing on the tiered memory hierarchy in mobile devices. Understanding this structure is crucial for appreciating how data is managed and why on-device AI memory limits become a critical performance factor.

Effective on-device AI relies on a carefully orchestrated memory hierarchy, and on-device AI memory limits directly shape how this hierarchy is utilized. This tiered structure is fundamental for efficiently feeding the compute units. The main system memory in mobile devices is typically Low-Power Double Data Rate (LPDDR) RAM. While it offers high capacity (e.g., 8GB to 16GB in many smartphones), it is physically separate from the main SoC, meaning data must traverse an interconnect, which adds latency.

Closer to the compute units, on-chip caches (SRAM) provide extremely fast, low-latency storage and form the foundation of modern on-device machine learning frameworks used across mobile platforms. SRAM, or Static Random-Access Memory, is a type of volatile memory that is faster and more expensive than DRAM. These caches (L1, L2, L3) are much smaller in capacity but are vital for holding frequently accessed data, thereby minimizing slower trips to LPDDR. Finally, flash storage (NAND, UFS) serves as persistent storage for the device’s operating system, applications, and the AI model itself.

Before execution, models are loaded from this flash storage into LPDDR.

Performance and Latency Constraints

This section examines the factors that limit the real-world performance and introduce latency in on-device AI. Understanding these constraints is vital for reconciling theoretical NPU capabilities with practical application performance.

The theoretical peak performance of NPUs in smartphones, often measured in Tera Operations Per Second (TOPS), may not fully represent sustained real-world performance. This metric indicates the maximum number of operations a processor can theoretically execute per second under ideal conditions. In fact, this peak performance is rarely sustained in practical applications due to thermal and power limits. Instead, real-world performance is frequently bottlenecked by the memory subsystem’s ability to supply data.

On-device AI memory limits, particularly bandwidth constraints, are a primary factor preventing NPUs from reaching their theoretical maximums.

While modern NPUs can deliver tens of TOPS, indicating significant computational power, this potential remains untapped if the data (model weights, activations) cannot be moved from LPDDR to the NPU’s registers and on-chip caches fast enough. This scenario often results in NPU cores sitting idle, waiting for data, a phenomenon known as “compute starvation” or being “memory-bound.” Furthermore, the arithmetic intensity of many on-device AI workloads, especially transformer inference at batch=1, is quite low. Arithmetic intensity measures the ratio of computations to data movement for a given workload. This means that for each computation, a relatively large amount of data needs to be moved, making data movement the dominant factor over the actual number of mathematical operations.

The following table illustrates typical performance characteristics for on-device AI:

| Metric | Typical Range (Mobile SoC) | Impact on AI Performance |

|---|---|---|

| NPU Compute (TOPS) | 10 – 45 TOPS | High theoretical peak for integer operations. |

| LPDDR Bandwidth (GB/s) | LPDDR Bandwidth (GB/s) | ~50–150 GB/s (peak, configuration-dependent) | Actual data throughput to compute units. |

| LPDDR Capacity (GB) | 8 – 16 GB | Total memory for OS, apps, model weights, KV cache, activations. |

| On-chip Cache (MB) | 4 – 32 MB | Fast, low-latency storage for frequently accessed data. |

- High NPU TOPS figures highlight significant raw processing power.

- LPDDR bandwidth, while significant, is often insufficient to fully utilize the NPU’s compute capabilities for large models.

- LPDDR capacity directly limits the size and complexity of models that can be loaded and executed.

- On-chip cache size is a critical factor in reducing reliance on slower LPDDR.

Power, Thermal, and Memory Limits

On-device AI memory limits are tightly coupled with power consumption and thermal behavior in mobile devices. Recognizing these constraints is essential for understanding the fundamental challenges of sustained on-device AI performance.

The physical constraints inherent to mobile devices—specifically battery life, heat dissipation, and physical space—are tightly coupled with their memory architecture. Moving data between different memory hierarchies (e.g., from off-chip LPDDR to on-chip SRAM cache, and then to NPU registers) consumes significantly more energy than performing the actual computation. This energy consumption must fit within the mobile power envelopes, which typically allow for only a few watts sustained. Power envelopes define the maximum power a device can consume without exceeding thermal or battery limits.

Consequently, this energy cost directly impacts battery life and contributes substantially to the device’s thermal profile.

When memory bandwidth is saturated or data is constantly being swapped due to capacity limits, the power consumption from data movement can become excessive. This frequently triggers thermal throttling, where the device proactively reduces performance to prevent overheating, leading to a degraded user experience. Aggressive thermal throttling behavior is a necessary safeguard, designed to protect components and maintain device stability. The capacity of LPDDR RAM itself represents a hard limit. For instance, a 7-billion-parameter LLM, even quantized to 2 bytes per parameter (FP16), requires approximately 14 GB of RAM for its weights alone.

This often exceeds typical smartphone RAM ceilings, rendering such models infeasible without further optimization and leaving little room for the operating system, other applications, and crucial runtime buffers like the KV (Key-Value) cache. The KV cache stores intermediate attention keys and values from previous tokens to accelerate LLM inference.

Real-World Trade-Offs

This section examines the practical trade-offs and optimization strategies employed to enable AI on resource-constrained devices. Understanding these compromises is crucial for appreciating the engineering challenges behind deploying effective on-device AI.

Engineers constantly make difficult trade-offs to enable AI on-device, carefully balancing model capability with hardware constraints.

- Quantization: Reducing the precision of model weights (e.g., from FP32 to FP16, INT8, or even INT4) is a primary technique to shrink both memory footprint and bandwidth requirements. These refer to different numerical precision formats, with lower numbers indicating fewer bits per value and thus smaller memory usage. This, however, can introduce a slight or sometimes significant accuracy trade-off.

- Model Pruning and Sparsity: Less important weights can be strategically removed from a model to reduce its size. This approach typically requires specialized hardware or software to efficiently handle the resulting sparse data, and it can also impact model accuracy. Sparse data refers to data where a significant portion of values are zero or negligible, allowing for more efficient storage and processing.

- Architectural Optimizations: Designing SoCs with tighter integration between compute units and memory controllers, or implementing unified memory architectures, can significantly improve data sharing efficiency and reduce latency. Unified memory architectures allow different processing units to access the same memory pool without redundant data copies.

- Context Window Limits: For LLMs, the “context window” (how much prior conversation or text the model can consider) is directly constrained by available memory. A longer context means a larger KV cache, which consumes more RAM. This directly impacts model size versus device feasibility, as larger context windows inherently demand more memory. Developers must thus choose between shorter, more consistent interactions or longer, more memory-intensive ones.

Edge vs Cloud Considerations

This section explores the fundamental decision between executing AI tasks on-device (edge) or offloading them to the cloud. This choice significantly impacts performance, privacy, and resource dependency for AI applications.

The decision to run AI on the edge is often dictated by on-device AI memory limits rather than compute availability. On-device execution offers compelling benefits such as lower latency, enhanced privacy, and independence from internet connectivity. It proves ideal for real-time tasks, sensitive data processing, and scenarios where network access is unreliable. However, these benefits are always weighed against the inherent power, thermal, and memory envelopes of local hardware.

However, when models exceed local memory capacity or bandwidth, or when computational demands are simply too high for sustained on-device performance, cloud fallback becomes a necessary strategy. This offloads the heavy lifting to powerful data center GPUs and their ample memory resources. Increasingly, hybrid approaches are becoming common, where simpler, smaller models run locally for immediate responses, while more complex or resource-intensive queries are seamlessly routed to the cloud. This strategy effectively balances the benefits of both environments, representing a practical system-level tradeoff to deliver robust AI experiences within device limitations.

Future Direction

Future research aims to overcome on-device AI memory limits through architectural and algorithmic innovation. These future directions are vital for unlocking the next generation of powerful and efficient local AI capabilities.

Research and development efforts are actively addressing the memory bottleneck with innovative architectural and algorithmic solutions. These efforts are not merely about increasing raw speed but fundamentally redesigning how AI interacts with hardware within stringent power and thermal budgets.

- Processing-in-Memory (PIM) / Near-Memory Computing: This experimental approach aims to perform some computation directly within or very close to the memory modules, to significantly reduce the energy and latency associated with data movement.

- Advanced Memory Technologies: While High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) is currently too expensive and power-hungry for most mobile devices, research into other 3D-stacked memory solutions and larger, more efficient on-chip caches continues. HBM is a high-performance RAM interface for 3D-stacked synchronous DRAM, offering significantly higher bandwidth than traditional DRAM.

- More Aggressive Quantization and Sparsity: Ongoing research focuses on pushing quantization to even lower bit-widths (e.g., 2-bit models) and developing highly sparse models that maintain accuracy, alongside enhanced hardware support for these emerging formats.

- System-Level Optimization: Continuous improvements in SoC design, encompassing memory controllers, interconnects, and power management, are crucial for maximizing the effective utilization of available memory and compute resources.

Key Takeaways

This section provides a concise summary of the most critical insights and conclusions from the article. These key takeaways reinforce the fundamental challenges and considerations for on-device AI performance.

- On-device AI memory limits often constrain performance more than raw compute capability, especially for large or sustained workloads.

- Large model sizes, especially for LLMs, frequently exceed typical mobile LPDDR RAM capacities.

- Data movement between memory and compute units is energy-intensive and a major contributor to thermal throttling.

- Quantization and model pruning are essential trade-offs for fitting models on-device, but can impact accuracy.

- Future advancements will focus on reducing data movement, increasing effective memory bandwidth, and optimizing memory architectures to enhance the capabilities of on-device AI.